![]()

Blog @ SunTech

Advice from the BP Measurement Experts

Blood Pressure Monitoring and Infection Control

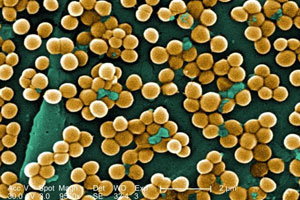

Infection control has long been a hot topic for acute-care hospitals, and has been the focus of patient advocacy groups, the popular press, and legislators for some time. Old stories of sponges and instruments being left inside patients by harried doctors and nurses have been supplanted by nightmarish scenarios containing ominous-sounding names like Clostridium difficile and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Unfortunately, for many patients in today's healthcare system, hypothetical scenarios and clinical studies have become a real matter of life and death. As a result, the spotlight is expanding to include other areas of the healthcare continuum-including long-term care facilities.

Infection control has long been a hot topic for acute-care hospitals, and has been the focus of patient advocacy groups, the popular press, and legislators for some time. Old stories of sponges and instruments being left inside patients by harried doctors and nurses have been supplanted by nightmarish scenarios containing ominous-sounding names like Clostridium difficile and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Unfortunately, for many patients in today's healthcare system, hypothetical scenarios and clinical studies have become a real matter of life and death. As a result, the spotlight is expanding to include other areas of the healthcare continuum-including long-term care facilities.

On September 30, 2009, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented revisions to Appendix PP - "Interpretive Guidelines for Long-Term Care Facilities," Tag F441. These revisions are causing clinical and administrative personnel at long-term care facilities to take a long, hard look at their infection control procedures.

Of particular concern are areas that are difficult to quantify and therefore open to some level of interpretation by surveyors, reviewers, and auditors. One of those involves the indirect transmission of harmful pathogens, which is defined in (F441) 42CFR 483.65 as "the transfer of an infectious agent through a contaminated intermediate object." Below is an excerpt explaining what is meant by intermediate objects.

The following are examples of opportunities for indirect contact:

Resident-care devices (e.g., electronic thermometers or glucose monitoring devices) may transmit pathogens if devices contaminated with blood or body fluids are shared without cleaning and disinfecting between uses for different residents

Certainly this would include blood pressure devices, such as manual sphygmomanometers and automated, oscillometric manometers, as well as the corresponding cuffs that are wrapped around a patient's arm. The document goes on to say that reducing and/or preventing infections through indirect contact requires the decontamination (i.e., cleaning, sanitizing, or disinfecting an object to render it safe for handling) of resident equipment, medical devices, and the environment. It also proffers the use of single-use disposable devices, pinning the choice of decontamination method on the risk of infection to the resident coming into contact with a particular piece of equipment.

The regulation relies on the same classification system adopted by the CDC, which identifies three risk levels associated with medical and surgical instruments: critical, semi-critical and noncritical. Here is how the CDC breaks it down:

- Critical items (e.g., needles, intravenous catheters, indwelling urinary catheters) are defined as those items which normally enter sterile tissue, or the vascular system, or through which blood flows. The equipment must be sterile when used, based on one of several accepted sterilization procedures;20

- Semi-critical items (e.g., thermometers, podiatry equipment, electric razors) are defined as those objects that touch mucous membranes or skin that is not intact. Such items require meticulous cleaning followed by high-level disinfection treatment using an FDA- approved chemo sterilizer agent, or they may be sterilized; and.

- Non-critical items (e.g., stethoscopes, blood pressure cuffs, over-bed tables) are defined as those that come into contact with intact skin or do not contact the resident. They require low level disinfection by cleaning periodically and after visible soiling, with an EPA disinfectant detergent or germicide that is approved for health care settings.

At first glance, this seems pretty straightforward. But with elderly long-term care residents, skin viability can vary considerably and conditions can change quickly. As a result, it is possible for an item like a blood pressure cuff, that is normally used on intact skin, to be used on a patient whose skin is not intact at the time the item is used on them. So would this be a ‘semi-critical' or a ‘non-critical' item, and how should it be treated from an infection-control perspective? What approach should administrators and staff take?

Replacing reusable semi-critical and non-critical items, including blood pressure cuffs, with disposable single-patient use versions is certainly one solution to preventing the spread of infection. But such a solution needs to make economic sense without sacrificing clinical accuracy. And since the economics of infection control are evolving quickly, there is no tried-and-true model for staff and administrators to rely on.

As long-term care facilities struggle with these kinds of issues, factors such as reliable clinical data, program costs, risk management issues, and even future demographic trends all come into play. How does your facility tackle this issue? What changes have you seen since the new requirements have been put into place? We're all ears.

Interested in getting more SunTech news, product info, as well as

tips, tricks, and insights from BP experts?

Sign up to get fresh content delivered direct to your inbox.